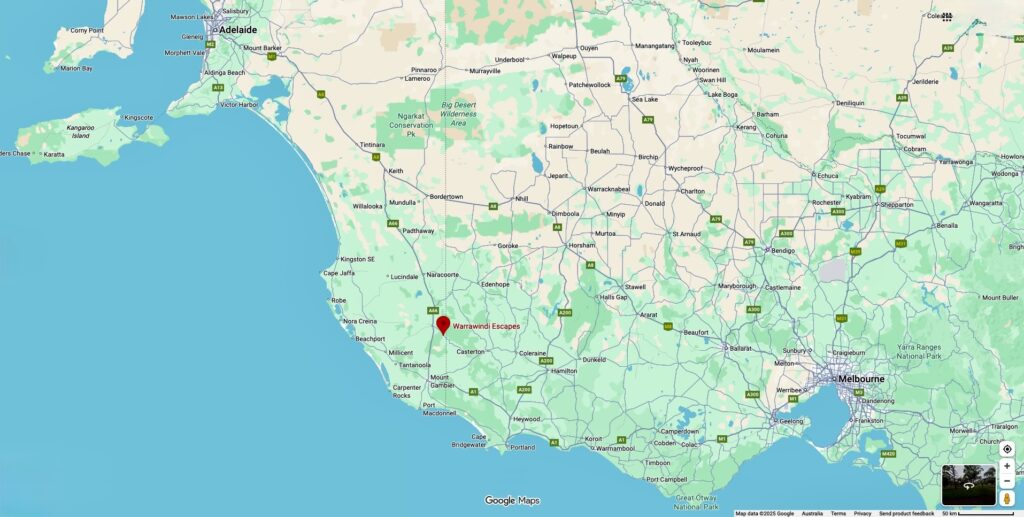

The sun drops across the plain at Warrawindi Farm, in the heart of the Limestone Coast, in South Australia. The last golden light skims a wide paddock where cattle share the grass with a few kangaroos and emus. A rare quietness settles over this 1,200-hectare property, only a ten-minute drive from the historic town of Penola, in South Australia’s Coonawarra, near the Victorian border.

Through the broad glass walls of two villas completed in 2025, the country opens in a sweeping 180-degree view. Light-filled and carefully furnished, they suit couples or families: one sleeps two (The Brolga), the other up to four with its 2 bedrooms (the Blue Wren). Each place keeps things simple and comfortable—an outdoor hot tub or an indoor spa bath, a fireplace for cool nights, a full kitchen, and floor-to-ceiling windows that turn every morning into a quiet show.

“Buried in the farm work, I first didn’t see how beautiful this place was,” says David Galpin. His ancestors came up from Adelaide in the 1880s—five generations back—to settle what would become Warrawindi Escapes Farm. Here, with his wife Alison, he raised six children and now watches fourteen grandchildren grow. “By showing the property to family and friends, I realised how fortunate I was to live here. Building the two guest houses was a way to share that beauty,” he says, with the quiet outlook of a man of the land.

Warrawindi is first and foremost a working farm, recognised for its cattle and for a steady shift toward regenerative practice: sharply reduced synthetic fertilisers, careful pasture rotation, native habitat restored, and soils brought back to health. Limousin, Hereford and Angus herds move across the paddocks, alongside sheep whose meat has a strong reputation across South Australia.

Here, farming and wildlife keep an honest balance. At first light and again toward dusk, David leads 4×4 outings across the property with the help of his partner, Coonawarra Experiences. Kangaroos, wallabies and emus step out along the edges of scrub and waterholes; brolgas—tall cranes known for their courtship dance—work the wetlands. The country also shelters a refuge for the red-tailed black-cockatoo, a rare, protected bird whose rasping call and heavy wingbeats often mark the Warrawindi sky.

At night, far from any glow of town, the southern sky opens in full. Guests in the villas watch a dense scatter of stars from their beds or the deck. A quality telescope sits ready for a closer look at the Southern Cross and the constellations of the southern hemisphere, under reliably dark, clear conditions.

Days can be kept simple—feet up, slow meals—or shaped around guided outings. Farm Tours in a 4WD run from 45 minutes to three hours and range across the property. The Sunset & Stars experience pairs the evening’s burnished light with stargazing after dark, capped by dinner on a timber platform David built on a small hill that looks out over the plain.

Fifteen kilometres from Warrawindi, the town of Penola (population 1,600) carries a reach well beyond its size. Mary MacKillop (1842–1909) lived here; canonised in 2010 as Australia’s first saint, she opened her congregation’s first school in a former stable. Her legacy still brings pilgrims and history-minded travellers to this pioneer town.

Along the main street, National Trust–listed buildings recall the early settler years, when Scottish and English pioneers took up runs on this country. Petticoat Lane gathers cottages from the 1850s through the First World War, some in local limestone with ornamented verandahs that echo the lines of British colonial architecture.

The Warrawindi stays and tours are part of packages offered by Coonawarra Experiences. To truly get a feel for the region, Simon and Kerry Meares created this local operator to run tailored, small-group tours in a LandCruiser, carrying visitors deep into the Limestone Coast.

Among the options, one of the standouts is dinner at Mayura Station. Founded in 1845, the property helped reshape wagyu breeding in Australia, and about a dozen years ago it opened an on-farm restaurant to showcase its beef. Here, full-blood wagyu are nicknamed “chocolate wagyu” for a diet that includes chocolate and sweets made in Australia. This unique approach has forged the station’s reputation. From the dining room or right at the Chef’s Table, guests watch as Chef Mark Wright brings each cut to life with talent, passion, and years of refined expertise. A performance as much as a meal.

On the plate, the Mayura wagyu tenderloin shows an even cut, quickly seared with a soft centre. The texture is silky, the flavours lingering—buttery with a trace of hazelnut. The Full-Blood Wagyu MB9+ carries dense marbling, a fine lattice of fat that melts slowly, feeding depth and juiciness into the meat. The first bite brings a near-caramel richness with notes of butter, hazelnut and a faint sweetness—an echo of the “chocolate-fed” diet. More than a dish, it becomes a sensory study, each mouthful building on the last, dense yet satiny.

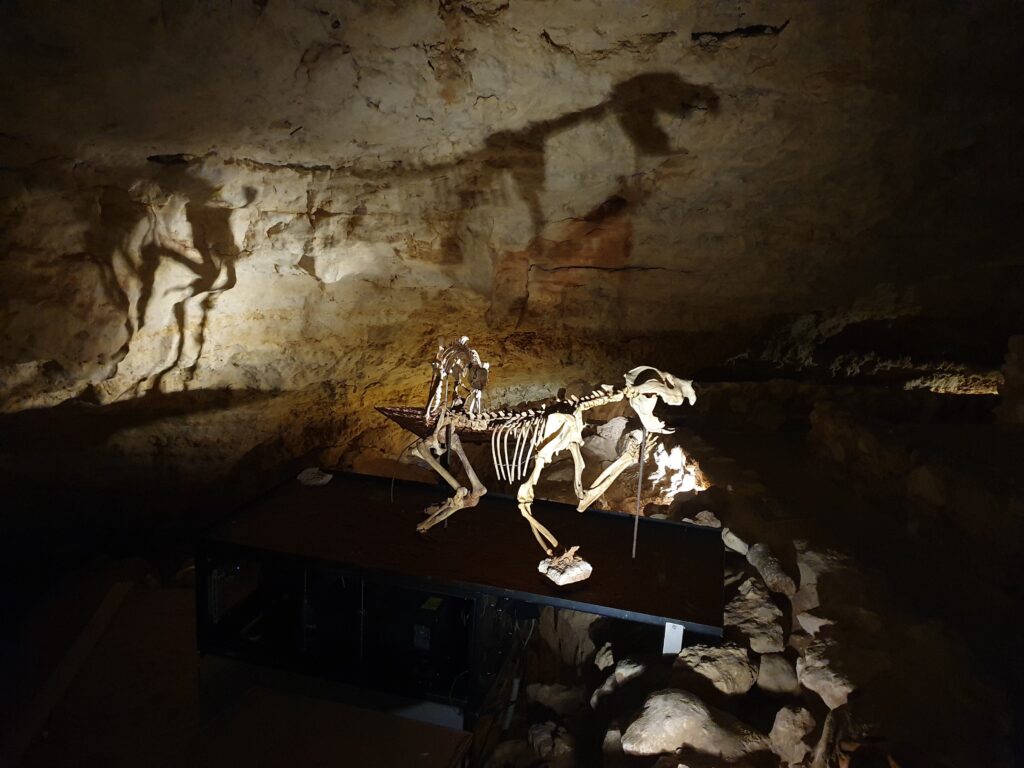

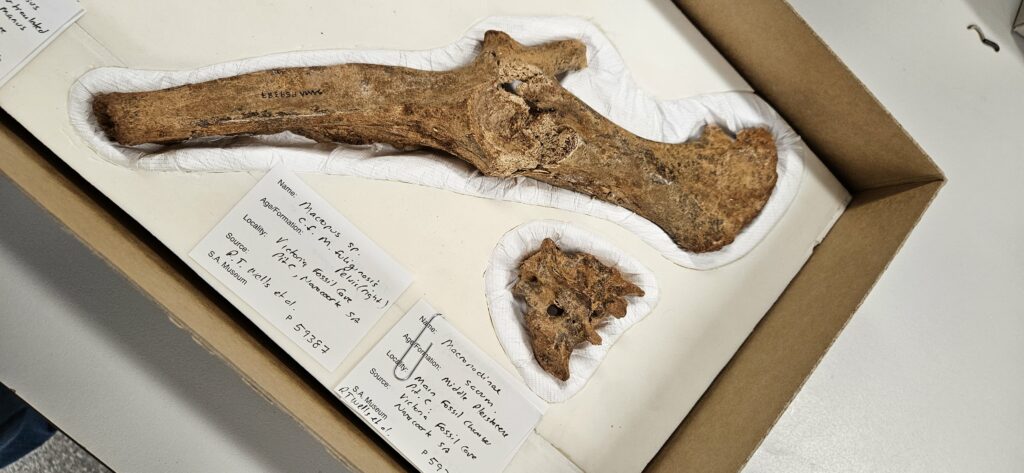

The next morning we set off with Simon for the Naracoorte Caves, about thirty kilometres from Penola. Listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site and counted among the continent’s key palaeontological records, the caves sit behind a quiet gap in the limestone reached by a track through forest. With the first steps underground, the air cools and the light drops. In the beam of a lamp the walls lift into time-worn forms—fine stalactites, folded draperies, columns built drip by drip. The silence holds, broken only by our footfalls.

In some chambers the floor reads like an archive: bands of sediment, bones set in place, impressions from creatures long gone. The fossils sketch Australia more than 60,000 years before Aboriginal people arrived—giant kangaroos, large reptiles, and the marsupial lion, a formidable hunter of the megafauna.

After the descent underground, the road swings toward the vines of Coonawarra. At Wynns Estate, founded in 1891, glasses fill with cabernet sauvignon shaped by the Terra Rossa—a narrow, fertile strip of red earth about 15 kilometres long and 2 kilometres wide. Iron-rich soils laid down millennia ago sit on porous limestone, letting the roots draw deep on minerals and shaping wines of quiet finesse.

As the guide talks through the vintages, aromas open and settle. The visit continues into the century-old cellar: thick walls, dark barrels, a hush that holds its own history. Here, the wine reads like a living archive, held in stone and time. Coonawarra is widely recognised in Australia for cabernet sauvignon.

The afternoon carries on 15 kilometres from Penola at Confido Coonawarra Olives. Centenarian trees sketch a landscape first planted by Mediterranean settlers who put down roots in this generous country.

Four years ago, Heidi Boyd fell for the grove and moved in to bring it back to life. Today she presses the fruit into oils with restrained, layered flavours, and turns part of the harvest into simple skincare drawn from that same tradition.

Another stop stays with visitors: meeting Trudy Taylor. Over twelve years, this quiet, retired postie has turned her 100-hectare property into a private refuge for orphaned kangaroos—most of their mothers killed on the roads. Only Coonawarra Experiences has permission to visit this place; other operators are not admitted.

In one enclosure, six young kangaroos find a patient foster carer, one of them barely two months old. Trudy tells how it began with a first joey found alive in its dead mother’s pouch. “I thought I’d feed him for a few months and then let him go,” she says, stroking the sleeping youngster. “But when more arrived, I realised this had become my job.” In South Australia, hand-reared kangaroos aren’t returned to the wild; they’re considered unfit for life in the bush. Today, around thirty adult kangaroos from the surrounding country still drift to the property, drawn by this quiet oasis—and, no doubt, by a reliable feed.

This morning, Coonawarra Experiences leads us into a new encounter: meeting Uncle Ken Jones, a Boandik Elder of the Pangula Mannamurna people, who has spent more than fifty years working for Country. Once a fisher and wildlife hand, later a writer and lecturer, honoured as a Lifelong Unsung Hero, Uncle Ken now walks the coast to share Boandik knowledge, land care, and the songs and stories that tie people to place.

His Explore the Coast walk begins at Port MacDonnell and traces rugged beaches, rock pools and cultural sites. He pauses to show bush foods and marine life, and to speak of living by tide and season. A small fire, fresh damper and story mark the pause. When the swell allows, the path bends toward middens and stone fish traps—traces of Boandik ancestors and their craft. The route shifts with the weather and the group, always closing with a grounded view of the Limestone Coast: salt on your boots, smoke in your clothes, and the sense of a Country that holds all other stories.

Guided by Simon and Kerry Meares, these encounters sketch the map of a region: dining at Mayura Station, tasting the cabernets of Coonawarra, walking through olive groves, spending a couple of nights at Warrawindi where cattle graze and stars crowd the sky, meeting Trudy Taylor and her orphaned kangaroos, stepping into the deep time of Naracoorte Caves, and following the coast with a Boandik Elder. Woven together, they tell the spirit of the Limestone Coast, and, in their way, of Australia itself !